THE POMEGRANATE GARDEN

Botany and Kabbalah in the Samarkand carpets

|

In the carpets presented in this catalogue a number of fascinating stories can be read as extraordinary as the events which contributed to interweaving them with time and making them endure. The carpets come from Uighur textile workshops which were active in the early 18th Century in the oases of Eastern Turkestan on the edge of the Taklamakan desert on the Silk Road, namely the oases of Khotan, Kashgar and Yarkand. In the West they were known by the name of Samarkand. (1)

If we examine the composition of the main motifs, the first thing to bear in mind is that these carpets appear to be the result of a coherent graphic design: to portray actual botanical tables. What we see before us is a pomegranate garden reproduced within the space of a carpet.

The fruit, which is arranged in sets of three so as to build up to a tree, which at times is sectioned and enlarged, becomes a circle at the centre of the carpet showing its sections full of seeds. The circular figures are also an orthogonal projection of the triad making up the tree. The flower of the pomegranate can be seen in its various stages of development, whereas the section of the ovary (2) is set out with just a few outlines and is often enriched by further decorations lying around it like a small crown. The seed grain is scattered through the whole field and the seeds are shown with their nucleus. In some carpets the whole of the central area is packed with shoots and young branches with buds, leaves and flowers. The corolla with its petals composes six- and eight-pointed stars and finally alternating sections of the calyx create a lattice with a positive-negative effect. This lengthy description might suffice to define the Samarkand carpets as Pomegranate carpets, but as is often the case, it is the less visible features which make the study most interesting.

|

The very idea of pomegranate carpet expresses a longing for the mythical original garden. A garden is the fantastic place in which to contemplate beauty and the mysteries of nature. A magic place, a safe haven, where man by tending flowers, plants and trees, nurtures the most intimate and delicate part of his being: a garden is a place of the soul.

A carpet is the reflection of this ideal place.

The carpet-garden allows man to satisfy his aesthetic and his spiritual sensibility and set aside a place for meditation and prayer. A space in which the stories of the world can be read, for those multi-coloured outlines are traces of myths and legends, principles and life forces, being and becoming and the cosmic cycle. The carpet, a small bounded and decorated space just like a garden, is thus itself a garden of the soul.

Scholarly research and investigation are often made up of coincidence and serendipity, and at times it is wisest to let oneself be guided by them. We came across another Pomegranate Garden, in Hebrew, Pardes Rimonim.

In this book, written in Safed in 1548 by Moses de Cordovero, the subject matter of the Zohar (3) and the kabbalistic writings of the Spanish period are systematically arranged and discussed.

The theme of the garden is the memory of Gan-Eden, the lost paradise so ardently desired by the mystics.

|

This image was one of the main metaphors in kabbalistic writings. The Kabbalah, or the "accepted tradition", is the esoteric doctrine established within the circle of the Sephardi mystic scholars (Sephardis being the Jews of Spainish origin) in the 13th Century.

Kabbalistic writings often refer to the pomegranate and the tree of life as representations of the sphere linked to the divine.

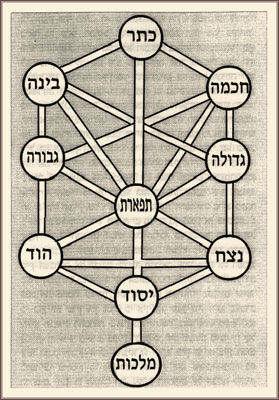

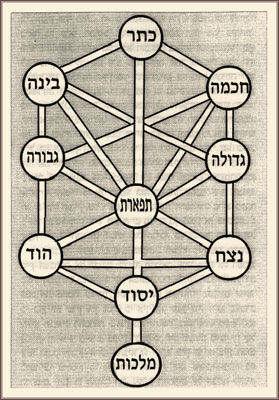

One of the plates contained in Pardes Rimonim, shows the Sefirot tree, the Tree of Life. It shows an abstract and symbolic diagram, comprising ten entities, called Sefirot, arranged along three parallel vertical pillars.

The Sefirot relate to major metaphysical concepts, to what are no less than levels within the Divinity. The Tree of Life in the Kabbalah is the plan used for the creation of the worlds, and the descending path along which souls and creatures have attained their current forms.

In the gematria, the doctrine which attributes a numerical value to every letter, the value of "Pomegranate Garden" is 700 which is equivalent to "the one Lord God".

The Pomegranate Garden is thus equivalent to an affirmation of faith. And it is this affirmation of faith which we find expressed in the carpets of the Oases.

Persecuted for many years, the Sephardi Jews were deprived of their belongings and their culture. Their identity was constantly questioned and their contribution to history systematically erased.

Since their books were burned, concealing mystical thought within other objects was, albeit unusually, a way to ensure its survival.

|

Tree of Spheres

from the Pardes Rimonim, 1548

by Moses de Cordovero |

Giulio Busi in the introduction to his book La Mistica Ebraica states that for mysticism, symbolism is a primary and unavoidable requirement, for it is the only thought system capable of intuitively penetrating the veil of the deepest mystery and which at the same time is a means of communication which allows for the message to be adapted to the level of knowledge of the recipient. The special nature of symbolic communication is that it is open to differing levels of interpretation, depending on the level of the reader himself... For those who know and who possess the right key for interpretation and the right sensitivity one single symbolic cue - even in pictural form - can open wide a world of analogies and implications. (4)

For example, in the motif of the tree of life, the multiplication of the subject, prior to having a decorative function, represents the expansion of an important idea, which conceals itself as it reveals itself. The symbolic function is potentially to link people around the same meaning, an experience which can be shared even by people of different generations, so as to create a bridge, a commonality of feeling and a spiritual affinity. (5)

At times, this bridge is also held together by small things such as a fruit tree: the pomegranate.

In all the cultures of the Near East, the pomegranate has always been seen as a symbol of fertility, fecundity and thus prosperity. This is because of the spherical structure of its fruit, its ruby red colour and the countless seeds it contains. In antiquity it was associated with the cult of the Mother Goddess. (6)

|

Stone Menorah

decorated with lilies and pomegranates

Synagogue of Hammat Tiberias

4th-5th century CE

Collection The Israel Museum, Jerusalem |

The ancient meaning of fertility of the pomegranate is re-affirmed more than once in the Torah in the description of the decorations and the furnishings of the Temple: "He made pomegranates in two rows encircling each network to decorate the capitals on top of the pillars". (1 Kings 7:18)

In Exodus instructions are given for the making of the priestly robes : "Make pomegranates of blue, purple and scarlet yarn around the hem of the robe, with gold bells between them". (Ex.28: 33)

In the verses of the Song of Songs the pomegranate is often mentioned in allegories of love and as a metaphor for female beauty: "Your temples behind your veil are like the halves of a pomegranate".(SS.4.3) "I would give you spiced wine to drink, the nectar of my pomegranate".(SS.8.2)

For Jews, today as in the past, the pomegranate also has deep emotional value because its representation always reminds them of the fruits of the Promised Land. (7)

In Deuteronomy, the pomegranate is one of the seven species of the Land of Israel, which is described as: "A land of wheat and barley, vines and fig-trees, pomegranates, olive oil and honey". (Deut.8:8)

|

Silver Shekel

from first jewish revolt against Rome

1st century CE

Collection The Israel Museum, Jerusalem

The inscription reads:

"Jerusalem the Holy"

|

After the destruction of the Second Temple (70 CE), it also became for exiles something which represented the memory of Jerusalem and their lost home. It is particularly significant that the only relic attributed to the Temple of Solomon is a small ivory pomegranate, which was probably used as a pommel on the sceptre of the High Priest (see p. 21). Equally indicative are the rimmonim, pomegranate-shaped adornments placed on the mantle enveloping the Sefer Torah, the Pentateuch Scroll used for Synagogue readings.

Starting as an ornament for the Torah Scrolls, the pomegranate became their very symbol, through the analogy between the seeds it contains and the 613 precepts of the Book . (8)

There are many bonds connecting Jews with the pomegranate. They are so numerous that it is a credible assumption that major concepts relating to religion, philosophy and identity were channelled through it, not only in poetic and musical allusions or in mystical allegories, but even more in everyday objects, such as pottery, copper and silver tools, fabric and, of course, carpets.

According to Scholem, the ideas, as well as a significant amount of habits and customs expounded for mystical reasons by the Kabbalists of Safed, spread without exception to all the countries of the diaspora. (9)

It was the Sephardi Jewish merchants who over the centuries travelled from the desert of Judea to Sefarad, from Granada (10) to the lands of the Ottoman Empire and all the way to the Far East who spread these ideas through the art of the carpets.

|

|

Pomegranate shaped bottle

provenance unknown

8th-9th century BCE

Collection The Israel Museum, Jerusalem

|

|

|

The Inscribed pomegranate, Ivory

8th century BCE

Collection The Israel Museum, Jerusalem

|

|

|

Rimonim

San'a

c. 1900

Collection The Israel Museum, Jerusalem

|

Historical sources give us a detailed picture of Sephardi merchants. The picture provided by the archives of the genizah (11) of the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Fustat for example, gives us an extraordinary general overview, describing as it does the complex profile of these men, who were not only merchants and travellers, but also Kabbalistic and philosophical scholars, botanical enthusiasts and passionately interested in astrology and astronomy. Who but someone with all this knowledge could have invented such complex products, as multi-faceted as a diamond ?

The Sephardi merchants who reached the oases of Eastern Turkestan in the 18th Century on their way East in search of new opportunities, were following in the footsteps of this intensely dynamic spiritual and trading tradition. Their knowledge of the art of carpets was that of the great Ottoman tradition to which they had themselves made vital contributions. An Arab traveller, Mustapha ben Abdullah Haji Chalfa, visiting the city of Thessalonika in the 17th Century had expressed his great admiration of the carpets manufactured by the Jews: "They knot their famous many-coloured carpets... nowhere else are they made so beautifully…". (12) The Sephardi carpet-workers renovated the production of Ottoman carpets, which was already of an excellent level, by introducing decorative features which had already been used in Spanish carpets. (13) Techniques and motifs such as the arch or the pomegranate began to appear in Turkish carpets after 1492, the year of the expulsion of the Jews from Spain. Both motifs are connected to the Jewish symbolic and liturgical apparatus. The arch resting on two pillars, similar to palms in the desert of Judea, is depicted on the cloth which still today in synagogues covers the aron ha-kodesh, the cabinet in which the Holy Books are kept. Almost as if the worshipper were invited to see it and imagine the Curtain protecting the Arc of the Covenant in the desert at the time of the Exodus. (14)

|

|

Oil lamps with pomegranate decoration

Judean coastal plain, Judean desert,

Israel and Jerash, Jordan

1st - 2nd century CE

Collection The Israel Museum, Jerusalem

|

They followed the routes already travelled by Jewish merchants acting as brokers in the silk trade with China. (15) China in the 18th Century under the Manchu dynasty had attained a high level of stability and prosperity and was on the verge of adding to its territory a new and vast empire in the heartland of Asia. Eastern Turkestan had always acted as a link between the West and China. In the first half of the 18th Century it was still self-ruling, for near the oases at the foot of the Tian Shan mountains, its ancient carovan centres were city states. (16) Khotan, Kashgar and Yarkand were among the most important centres and all had a long-standing weaving tradition. The archaeologist Sir Aurel Stein, who made major finds in the area of the oases, believed that the craftsmen of Khotan had been able since ancient times to develop a composite style in their textiles and carpets so as to accommodate the tastes of both the East and the West. (17) In the representational tradition of the region, pomegranates had always been much loved and portrayed and were associated with propitiatory lunar rites. (18) In the first half of the 18th Century, a number of Sephardi merchants settled in the oases of Eastern Turkestan. They remained there for a generation, until the Chinese annexation of the region in the latter half of the century. It was they who transformed the small crafts shops of the Uighurs into factories which could produce the outstanding quality carpets called Samarkand.

The name of the city of a hundred domes marked the fate of the carpets, making them more attractive to the wealthy purchasers of the time, such as those who lived in the great palaces of Mughal India and the Pavilion of the Forbidden City in China. (19)

The Chinese conquest of Eastern Turkestan caused an increase in the output of carpets, essentially because of the greater degree of social organization which resulted in the oases. Gradually the motifs and symbols used initially were adapted to traditional Chinese iconography. (20) Even the borders, which until then had been framing devices with plain, simple motifs begin to show more elaborate designs. (21)

|

|

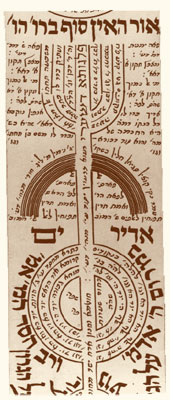

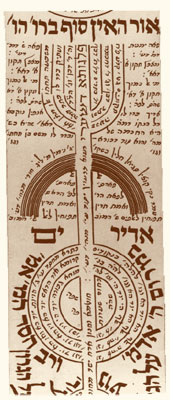

Tree of Spheres Amulets

Germany

18th century

Collection The Israel Museum, Jerusalem

|

|

|

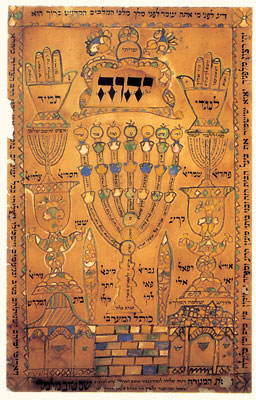

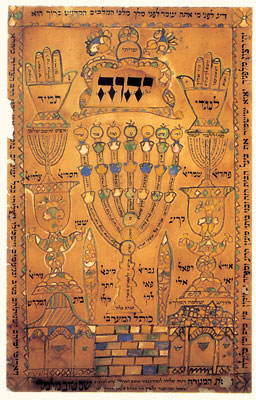

Shivviti plaque with holy places

Hebron

second half of the 19th century

artist: Shneur Zalman of Hebron

Collection The Israel Museum, Jerusalem

|

In Indian thought the Cosmos is seen as a fabric, a huge warp. Air (vayû) wove the universe connecting together as with a yarn this world and the other and all human beings (Brhadaranyaka Up.III,7,2) in the same way that breath (prana) wove human life. (Atharva Veda x, 2,13). In the cosmos as in human life everything is bound by an invisible fabric. (22)

Since earliest times, man has compared the structure of the cosmos to that of a net, a fabric and a carpet in order to decipher the mystery of creation.

The pomegranate carpets re-iterate the analogy. "All is linked to the all, down to the last link of the chain …/… and all forms of existence are linked to each other and involved in each other". (23) The harmony and the balance they express show once again the close, inseparable bond between aesthetics, mysticism and science.

The makers of these pomegranate gardens imbued them with all the wisdom, love and faith they possessed so as to make them a reflection of their own souls.

The need to narrate oneself through images has impelled human beings to search for and use symbols having suitable forms and to select them from the figures of nature. A symbol is alive when it makes one dream, not when it refers back to thoughts which have already been thought. (24)

The pomegranate is one of those symbols with many different meanings and which is recognizable and understandable because it belongs to the collective imagination which is our common heritage and which artists through the ages have tapped to create their works. The appearance of this fruit also expresses a concept embraced by both the Kabbalah and modern physics, the theory of the potentiality of all possible events.

References

(1) A brief bibliography relating to carpets from Eastern Turkestan:

Bidder Hans, Carpets from Eastern Turkestan, Known as Khotan, Samarkand and Kansu Carpets, New York, 1964. Eiland Murray L., Chinese and Exotic Rugs. New York Graphic Society, Boston, 1979. Ellis Charles Grant, Chinese Rugs, Textile Museum Journal II/3 (1968), pp. 35 - 52, 1968. Oriental Carpets in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, pp.264-286, 1988. Haskins John F., Imperial Carpets from Peking, University Art Gallery, Pittsburgh, 1973. Lee Yu-Kuan Sammy, Art Rugs from Silk Route and Great Wall Areas, Oriental House, Tokyo, 1980. Lorentz H. A., A View of Chinese Rugs, from the Seventeenth to the Twentieth Century, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, 1973. O'Bannon George, Rugs of East Turkestan: Khotan, Yarkand or Kashgar? Oriental Rug Review, vol. XI, August/September, pp. 16, 1991. Rostov Charles I. and Guanyan Jia, Chinese Carpets, Harry N. Abrams, New York, 1983.

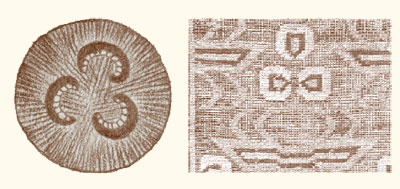

(2) The motif called "Chintamani" may bave a botanical origin.

|

|

Pomegranate-transverse section

of lower chamber of fruit.

|

Chintamani motif. |

(3) Sefer ha-zohar, the Book of Splendour and the absolute masterpiece of the Kabbalah, attributed to Moses de Leon de Granada, who wrote it in the 13th Century in Castile.

(4) Giulio Busi, Elena Lowenthal, a cura di, Mistica ebraica, testi della tradizione segreta del giudaismo dal III al XVIII secolo, Torino, 1995, p.XIII.

(5) The Affinity of souls is an important concept of Luria's defined as Tiqqun which states that some souls are interrelated and there are even families of souls… they have the special ability to help each other and to complete each other through their actions. G. Scholem, Le grandi correnti della mistica ebraica, Torino, 1993, pp.289/290.

(6) Maria Gimbutas, The Language of the Goddess, 1989.

(7) On Rosh ha-Shanà, the Jewish New Year, it is customary to place a pomegranate on the table which has been laid for the celebration.

(8) Giulio Busi, Simboli del pensiero ebraico, Torino, 1999, p.286.

(9) Gershom Scholem, op. cit., Torino, 1993, p.291.

(10) Granada means pomegranate and the shield of the city bears many variations of a representation of a pomegranate or a tree of life. AA.VV., La impronta en Granada, Granada, 1997. The Arabs who conquered it in 711 called it Granath al- Yahud, pomegranate of the Jews, since so many lived there.

(11) S. D. Goiten, Una società mediterranea, Milano, 2002. A genizah is a deposit of objects, both sacred and not, which can no longer be used and which in any case were destined to be disposed of, usually by means of a solemn burial. In the genizot, everything written in the Hebrew alphabet, from religious texts to business letters was carefully kept. The documents have survived thanks to the dry Egyptian climate, however a genizah was built to last and its function was more ritual than archival. Materially, it had no windows and doors but only a single hole in the wall below the roof so that a ladder had to be climbed to gain access.

(12) Emmanuel I. S., Histoire de l'industrie de tissus de Israélites de Salonique, Paris, 1935, p.18 note 25 b.

(13) The most ancient testimony of Jewish carpet-making are from Spain. A. Felton, Jewish Carpets, Woodbridge, 1997,p.24.

(14) The use of an arch resembling a palm tree in Ottoman prayer carpets derives from Jewish influence. Palme e Preghiere, Textilia, Roma 2000.

(15) Jews in old China, edited by Sidney Shapiro, New York, 2001.

(16) The earliest information on Central Asian city-states is provided by Han dynasty sources and establishes their existence as early as the 2nd Century CE L. Boulnois, la Route de la soie, Geneve, 1993, pag.65.

(17) The weaving tradition of Eastern Turkestan has also been confirmed by archaeological findings: Tesori del Xinjiang, due tappeti da nuovi scavi, Li Wenyng, Ghereh, X, 2002. The carpets were found in 3rd and 4th Century burial sites.

(18) One of the local cults in Central Asia was devoted to Anahita, a divinity of the Amu-Darja, goddess of waters and fertility, who holds a pomegranate in her hands.

L. Boulnois, op.cit., p.161.

(19) Textilia, Cina 1644-1911,Tappeti di seta e di metallo della Città Proibita, Roma, 1998.

(20) The motif of the circle is always a metaphor of the divinity but is now associated with Buddhism. In some compositions, constellations recalling the astrological signs of the zodiac are depicted, in others, the mating ritual of butterflies around the flower, which indicates courting between young lovers. The sections of flowers are sometimes interpreted as clouds or animals and elsewhere as stars, whereas the pomegranate seed grains are considered to be rings. The small pomegranates evoke good fortune and longevity and the carpet itself takes on the properties of a powerful talisman which can dispel the forces of evil and extends the promise of all sorts of blessings.

(21) There are two main trends impelling the evolution of borders in the history of carpets. One sees them as integral parts of the carpet so that not only are do they share in the harmony of the composition but are also consistent in terms of symbols. The other approach is to consider the function of the border as being the same as that performed by a frame for a painting. Consequently, the symbols used are also independent of the main body of the carpet.

(22) Mircea Eliade, Immagini e simboli, Milano, 1993, pag.104.

(23) Dal Sefer-harimon - il Libro del Melograno, Mosè de Leon de Granada, 1287.

(24) Denis Gaita, Il pensiero del cuore, Bompiani, 1991, pp.98/104.

|